“A look at the notion of containing through chosen pieces from the European tradition”

KFSTA MA Traditional Arts, Summer 2019

•

People have an inclination to encase what is precious and there can be an endearing solemnity and profundity in the act of containing what is beloved. Hiding and veiling, for safety, privacy and exclusion of use is an act often overlooked due to its humbleness and commonness. This tendency to contain valued possessions is paired with another - to embellish the container, to make it personal, appropriate, and above all beautiful.

In the course of this essay I will look at the various ways of encasing through art pieces which have inspired me and for which I have had an affection over a long time. These pieces come from across Europe, an area which I consider my mind’s and heart’s home, and also the place where my family has came from for generations. By no means do I find these to be the finest exemplars and I wish I could have had time and space to investigate the many fine objects from other cultures which relate to my topic of interest. However, due to limitations of this essay, I have narrowed down my field of examples to the ones which I see as a coherent whole, with links in the outside world and that inside myself.

As a conclusion I will look into how enclosing, be it physical or abstract, can become an attempt to return to one’s prime comfort and safety and how this concept might be at the root of my long running interest in the notion of encasing. I will also look at the now common lack of embellishments on objects of everyday use, the so called minimalist objects, which are to my view a reaction to the overwhelming factory mass-production.

The Stele Giustiniani [image 1], named after its former owner in Venice and now housed at the Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen, Belin, a Partian funerary monument carved in relief around 460BC, has a captivating depiction of a young woman caught at the moment of a supposedly mundane action. Peering into her jewellery box, the carving sensitively rendered a moment of the lady’s everyday life and through that instant of her life, encapsulated the melancholy of passing - that of youth and of a life. Our existence is in its large part composed of a chain of repeated moments of daily poetry. The stele has a still-life quality, strengthened by its now monochromatic colour, capturing for centuries an instant otherwise ephemeral, passing without much trace, and yet a moment which is charged with the emotion of the fragility of our life. It leaves me forever wondering over her life, her love, her fortune or misfortune and her premature death.

Another piece which in my mind I pair with this one, is the Stele Hegeso [image 2], most likely sculpted by Kallimachos between 410-400 BC, currently at the National Archeological Museum in Athens. Once again an everyday moment captured in stone, a fleeting vision caught for centuries. The young noble lady is shown while choosing a piece of jewellery to beautify herself on that one particular day. A day which turned out to be the one for eternity. Her attention fixed on the detail of her jewel, originally rendered in colour paint, but obliterated over the centuries, which makes for a poignant irony on the value of earthly riches.

Apart from their aesthetic beauty and serenity, so aptly depicting the melancholy and inevitability of the passage of time, these two images have always captured my attention for their inclusion of a pyx as a central point of their imagery.

“Pyx: from Latin ‘pyxis’ small box, from Greek ‘puxos’ box tree” 1

The pyx, in its many forms and variations, has served women of different classes to hold their riches. From jewellery through trinkets to love letters. Things private and of the heart, whether virtuous or shameful, a world in itself, reserved solely for its owner. Through the central placement of a pyx on both stelae, an object personal and intimate, we are let in on the ladies’ secrets. We could almost start to feel ourselves intruders, was it not for the serenity of the carving and the now bare colour of the stone. The intimacy of these scenes draws us into a silent world of meditation, directing us through the almost banality of everyday actions to the profundity of the passage of time.

Our reading of these sculptures can not be as it was for those it originally addressed, but, as is with all brilliant art, they carry a manyfold, enduring story for any generation. For myself, they poetically refer to our life as a box opened, a fleeting moment, a jewel chosen, worn for a timespan of a day and thence returned to the source. The simplicity and yet profundity of the moments, caught through the mastery crafting, never ceases to make me wonder at the visual poetry held so gently, yet firmly over the centuries.

These Greek ladies, revealed to us through their garments and head-wears as of a higher social status, had their equivalent in a descendant society, centuries later, in what we now call Italy. It was a custom there among the elite at the time of the Renaissance to have, before the wedding, chests ordered by the future husband and sent to the bride’s house to be filled with her dowry. These were the cassoni, elaborately decorated Italian marriage chests, and were then carried in the marriage procession to the husband’s house.

“The shape of this chest and the relief decoration on the front reflect the influence of ancient Greek and Roman sarcophagi.” 2

The container’s form, taking its root in the funerary sarcophagus, makes perhaps an unintentional link to the Greek stelae described earlier, and so has the theme of life, with marriage as its pivotal point, meet the inevitable death.

Fifteenth century cassoni were decorated with pained panels, with intarsia inlay and with scenes in pastiglia, a gesso applied in layers and gilded. The scenes depicted were often from Ovid and other Roman poets, mythological fables of love and fertility, as well as chases, hunts and jousts, the contemporary symbolisms of love. Some chests were lavishly ornamental.

"[...] one might remember the almost unbelievable importance once given to all objects designed to keep various goods and chattels. This is the great period of the chest and casket” 3

The cassone was not a mere container, as if a suitcase would be today. Its form and decorative design formed a coherent whole with the goods it held. Often at the time the container was produced solely for the purpose of keeping one particular object. There was often a personal relationship between the owner and the object encased but also between the container and that which it held. This holistic approach required deliberate decorations with a close relation between the themes and the purpose of the object.

“The [...] box has been turned into the subordinate merely technical component of a fanciful work of art as the panel or canvas is in a picture.” 4

The ‘Onesta e Bella’ forzerino, a flamboyant Florentine engagement chest, now at the V&A, made ca.1400 [image 3], has its panels decorated lavishly with gilding and the then very expensive blue. Its panels display hunting scenes, the fountain of love and the wounded stag, contemporary symbols of love, understood as a chase.

“Lady, [...] I am a knight of Little Brittany. Yesterday I chased a wonderful white deer within the forest. The shaft with which I struck her to my hurt, returned again on me, and caused this wound [...] that never might this sore be healed, save by one only damsel in the world” 5

The forzerino was a gift of a future husband to his prospective wife. With the couple, as often was at the time, unable to meet in person prior to their marriage, the gifts were the scarce means of communication. Therefore, the box, as well as its contents, were charged with meaning. The images of love on the forzerino panels stirred the young woman’s imagination and thence her mind and heart into affection.

“[...] bride receiving the rich forzerino from that husband whom she never saw, she feels much beloved when she is so richly rewarded, and she creates a noble image of him who so nobly sends.” 6

The container not only enveloped the riches, but also the message of the man’s noble intentions and was given in hope of an equally noble requite in order to ensure a future of fidelity, devotion and regard. The container was made with a precisely defined use in mind and its decorative programme was entirely incorporated into that very distinct and exceptional purpose of the forzerino.

The young woman will adorn her body with the precious gifts, clothing and jewellery sent by her future beloved within the forzerino. Soon her body will also contain. Traditionally protected by society and religion, through the notion of sexual chastity held until marriage, the female body, the sacred container of the mystery of a new life, another human being.

Our skin holds inside itself the body, the soul and the heart. Our skin contains us in a sense. And we decorate ourselves, with clothing, jewellery, tattoos. Some such decorations denote the contained, a crown denotes a monarch, a habit a spiritual person and so on. A young bride decorates herself according to a custom, as a craftsman would embellish a container, and as a mystery encased, she will go to her husband’s house.

An enclosure, boundary, keeps within and keeps away, as does marriage. It keeps the married persons within its bonds, with neither her nor him any longer available to the world. The Unicorn in Captivity [image 4], a 15th century Netherlandish tapestry, now kept at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has been given multiple readings of which we can probably never be certain. In religious light, the animal is likened to Christ and his lady to the Virgin Mary. It has also been given a secular reading which tells of a man’s captured heart, the beloved tamed, embraced within the garden of vegetal symbolisms of love and fertility.

Plants growing in their giardino dell’amore echo the theme of their marriage: the aphrodisiac wild orchid, the flaming colour of the carnations emblematic of love, the wild strawberry denoting seduction and the sensual pleasures of this world. 7

Most of all it is the pomegranate, bursting and dripping its sweet contents over the unicorn’s body. The stains are no longer blood of the wounds sustained during the hunt. The bright markings are now that of the delightful taste of love.

“[...] pomegranate was said to have been the only tree that Aphrodite planted in Cyprus. Hence it was an attribute of Venus, the goddess of love.” 8

The unicorn is said to be remaining voluntarily in his captivity. His enclosure could be likened to the marriage ring, the fence of affection, an imprisonment sweet and desired.

“Sona ‘a battenti, sona chitarra mia,

li colpi giusti lo sonatur ti dà.

[...] ruspiti da lu sonnu non cchiù dormire e non ci dormi quannuu c'avimmo amari. Nu letto di viole ci lu faciti,

[...] e li cuperti soni di vasilicoi.” 9

Flowers have not ceased to envelop symbolisms of love for those who follow tradition, as the contemporary singer who wrote the above song. The words of traditional songs, with their rich symbolic references, once widely understood, but now lost to most people, are as if cassone closed. The majority of us find we no longer have the key to these wealths. With symbolism no longer legible or even used, we communicate in bare a=a manner. Nuances are no longer present.

Music is the most potent vehicle for poetry. Traditional music, being thoroughly tested and free to all, is its most trusted variant. Poems sung or declaimed, with their abundant allusions, are as if containers filled with richness of sentiments, desires, life’s truths, and love in all its dimensions. However, the cited song is a rare occurrence, with our contemporary music being, in its majority, either vulgar or poignantly plain in its sentimentalism. If love, and more so lovemaking, is described in terms other than poetic it soon runs into the vulgar. With the metaphorical and symbolic gone, we have rid portrayals of love of its many invisible dimensions, of its beauty, brining it down to a description of a bare physical act. We are starved of the only language capable of a description of the mystery of love with its multifold appearances. Therefore, I wish to repeat after the singer:

“Sona ‘a battenti, sona chitarra mia” 10

The language encases meaning, and within its power is to pass over a message, a knowledge, a belief. The many oral traditions, alive until recent in every corner of the world, humble and therefore now often undervalued and overseen, were always powerful and potent, albeit invisible, containers for some of the most profound wisdoms passed down to us over the centuries.

The traditional song has been as if a travelling box, happy to share its contents with anyone willing to sing it. Moving from one place to another, free as a bird, enclosing in its tune the joys and laments of a heart, only to be unraveled and disclosed to another.

“Quell’augellin, che canta

Si dolcemente [...] ‘Ardo d’amore’

E chiama il suo desio.

Che gli risponde ‘Ardo d’amore anch’io’ Che sii tu benedetto,

Amoroso gentil vago augelletto.” 11

Indeed, blessed are the birds which can burn with love and enclose the message of their affection within their sweet song. Their interchange is shielded, encased, kept safe, protected by the intelligibility of their warbling, a language so mysteriously understood between their own kind.

“The language of birds is very ancient, and, like other ancient modes of speech very elliptical: little is said but much is meant and much is understood.” 12

The language encases meaning, and within its power is to conceal a message, or to disclose it.

The mentioned chitarone, is yet another form of a container, as are many musical instruments and the human throat. These contain the most captivating, immediate and universal form of communication - music. Many historical instruments have exquisite, lace like carved decorations at the very space where the sound meets the outside world. The entrance to the instrument, to the confined and mysterious space so pregnant with emotion and beauty if handled by a skilful lover, forever ready to pour out its abundance and saturate our withered hearts. The instruments were fashioned with as much attention and care as the mentioned cassone by the master craftsmen.

“One imagines the handsome clean board, skilfully treated, [...] essential and precisely proportioned to the diameter, and the whole well glued and finished. The purist would be delighted by the perfection of workmanship and design, respect for the medium and the purpose, it could not be better in the machine age; and the reformer, addicted to modern urbanism, would complain that the self-evident beauty of such a perfect utilitarian object has been debased by absurd conversion. To add another truism one should reply that mankind likes and needs also something else, suggestive, imaginative and sometimes even in an object of daily use.” 13

Although written over half a century ago, this is an apt comment on how much the modern aesthetic criticism sees decoration superfluous, sentimental and a spoiler to the bare beauty of the material and form, misunderstanding the concept of embellishment. The impersonal, minimalist objects of daily use mass-produced for us today are made for their practical application. The objects are no longer vehicles for any customs and carry no widely understood messages. The minimalist bareness can only be filled with meaning if the object is given and received within a personal relationship between individuals willing to give it such an interpretation.

This celebration of pure skeletal form and bare material can be understood if we see it as a reaction to the omnipresent, cheaply available, often ugly objects, stripped of any artistic value, with a cornucopia of decorative references, but all too dislocated and disassociated. The modern embellishment is culturally neutral or simplified, designed in a distant place, it has a foreign heritage or a random mix of sources, becoming unintelligible to the potential buyer, who with time becomes oblivious to its potential deeper meaning. The same plastic Made in China boxes are available in chain stores throughout the world and their decorations, on most occasions, do not relate to the cultural heritage of the place where they are sold.

We are over-flooded with artificially coloured, badly produced, factory made trinkets in cheap materials and the rebellious stripping of objects to their bare minimum and solely to their core functions seems like an attempt to catch an aesthetic gasp of fresh air. It also could be perceived as an attempt at universal aesthetics, which, in the global village, could perhaps strive to unite amid the confusion of heritage of the multi-cultural societies.

However, I also sense in this religious refraining of use of embellishments a fear to make the object personal and rooted in a particular aesthetic tradition and therefore, a fear of attachment, adherence and choice. More importantly, I see it as aesthetic and poetic poverty, almost starvation. The answer, I would argue, is not to rid the objects of their decoration altogether, but rather to learn once again to cherish the natural material and the traditional embellishment, to learn to choose them wisely and for a reason, reconnecting to the narrative and aesthetic heritage.

Our minds and hearts need visual poetry. The beautiful, mysterious, suggestive, metaphorical are means by which whatever is beyond us can become more accessible, enveloped in a story, in a poem, in a symbol.

Visual and verbal poetry feeds our inner worlds housed in our skulls, in themselves handsomely modelled by our creator. As if our personal libraries, our skulls hold our memories, feelings, thoughts, deliberations, confusions, all the flavours and happenings of our lives. Our skulls are containers of our consciousness and the mechanisms by which we take in the world, make decisions of what is right and what is wrong, what is love and what isn’t, what is beauty and what is not, where is life and where is death.

“there was being extinguished merely a world of petty cares in the breast of a slave - the tea to be brewed, the camels watered [...] revived by a surge of memories, a man lay dying in the glory of humanity. The hard bone of his skull was in a sense an old treasure chest and I could not know what coloured stuffs, what images of festivities, what vestiges, obsolete and vain in this desert, had here escaped the shipwreck. The chest was there, locked and heavy. I could not know what bit of the world was crumbling in this man during the gigantic slumber of his ultimate days, was disintegrating in this consciousness and this flesh which little by little was reverting to night and to root.” 14

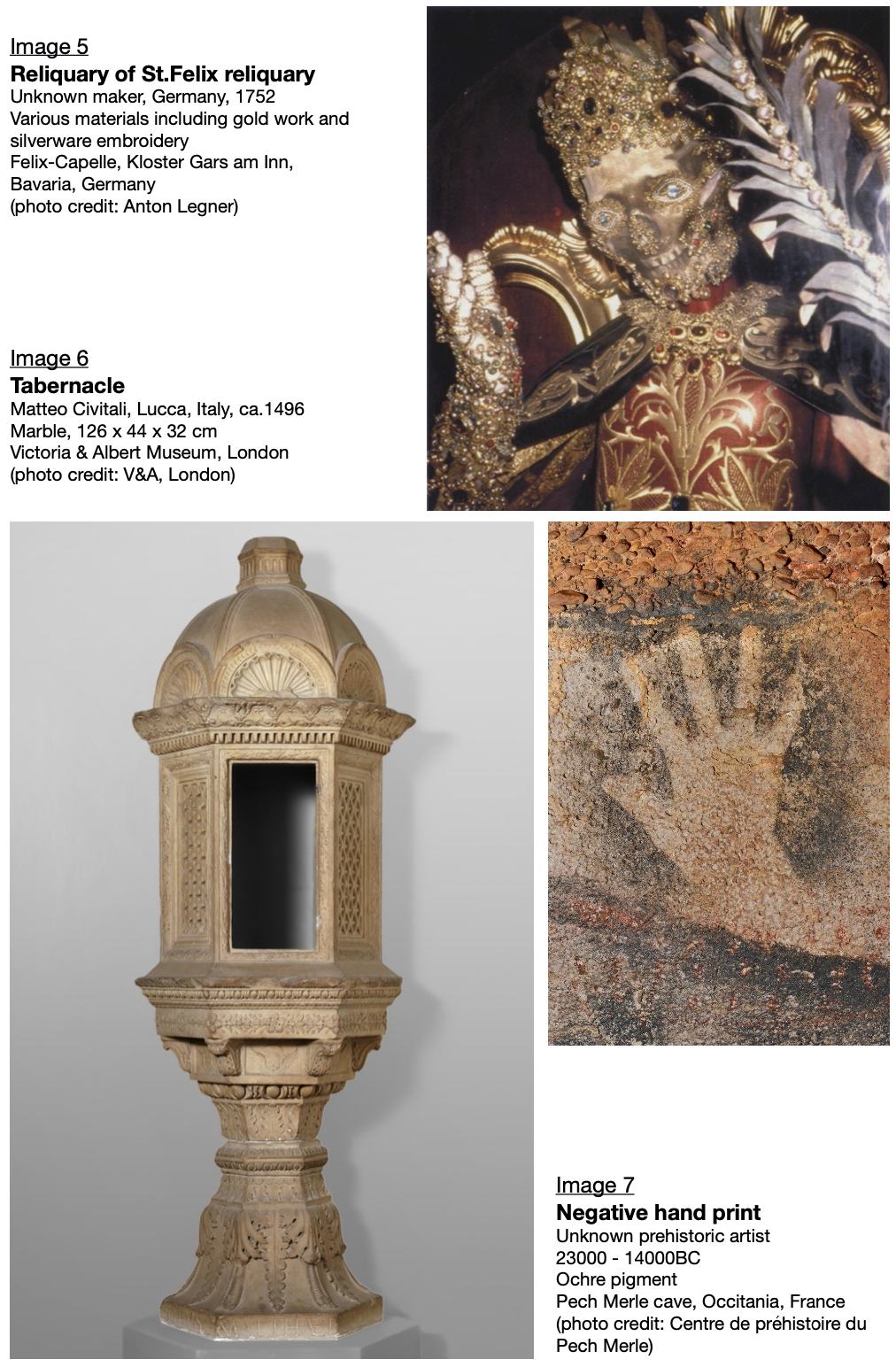

The skulls of saints were preserved inside beautiful reliquaries or displayed, decorated with precious jewellery, as in the case of St.Felix at the Kloster Gars am Inn, Bavaria [image 5]. The process by which heaven is reached is tangible and realistic. It happened there, in that spherical space of bone, through battles with desires and doubts, deliberations and choices which informed actions and hence led the man to God, sainthood and heaven. The reliquary containers often had their form mirror the contents, and their lavish decorations made it clear that the contents were

“more valuable to us than precious stones and finer than refined gold” 15

It is the container in its many forms, the act of containing, and the state of being contained, which is the subject of my essay. A container as a means for us to enclose that which we hold dear, a treasure of value either worldly or personal or both. Possessions which should only be taken out of their protective encasement with care, examined with due reverence, admired, used for a given, usually brief period of time and replaced back in the receptacle. The jewellery is returned to the pyx, the soul to God, the body to soil, the song to the instrument, the marital riches to the cassone.

My first and strongest encounter with a container of something held precious was in the place where I have spent much of my childhood days, my parish church. The tabernacle holds the biggest mystery for a catholic believer - the Holy Eucharist. The most precious material object in the universe, the most beloved, most delicate, tangible piece of matter, the Bread of Life. For many it seems absurd to protect a piece of bread, to ‘clothe’ it in gold and jewels, but its value can be understood solely with the believing and trusting heart.

A fine example of this type of container is the tabernacle made in Lucca, Italy, ca. 1496, by Matteo Civitali, and now housed at the V&A [image 6]. With its intricate patterns carved in marble, the detailed craftwork bearing witness to the love and veneration of its contents. The Eucharist was held in a ciborium, a lidded cup, or in a pyx and then placed in the tabernacle. The hard material was transformed by the craftsman’s hand to a lace like quality, indicating the gentleness and extreme fragility of the treasure par excellence which it contained. Inside the tabernacle, as if in the Virgin Mary’s womb, God incarnate.

But why is it that that which we hold dear, we do not wish to have on permanent display? There is a need for secrecy in us, for privacy, for things to be held away from sight, the need for a hortus conclusus,

“enclosure and containment, something warm, protective and nurturing, a place for incubating life.” 16

I wonder how much of our need to protect our prezioso in a darkened, sheltered space is a reminiscence of the prenatal safety of the womb. Would it be, that our desire for the protection of our riches, be it material, sentimental, intellectual or emotional is also an act of protecting that which somehow gives us life? The Eucharist gives life to the soul, the jewel enlivens a wife’s beauty, a keepsake rekindles a love. Treasured objects, kept aside and away become potent through their exclusion from view. A synonym for the word contain is cocoon, “to envelop in a protective or comforting way” 17

Elaine N. Aron, in her book on heightened sensitivity, mentions our need of the various forms of containment in our life which can offer us safety and protection.

“Some of the most important containers are the precious people in you life: spouse, parent, child [...]. There are even less tangible containers: your work, memories of good times [...] your deepest beliefs and philosophy of life, inner worlds of prayer and meditation.” 18

Considering the unrestful times which surrounded me during childhood, and the silence and peace I found at that time in my local church in front of the tabernacle, I find the need described by Elaine N. Aron, at least a partial reason why the notion of containing has always captivated me.

I can clearly recall two other containers which enchanted me and fed my imagination at that early time of my life. One was an antique clock, in dark mahogany, with a porcelain face. It had a small door with a latch on its side which to my then mind was a door to all sorts of silent worlds. The other was a marquetry cabinet, about 40cm in hight, with a set of double doors opening to the sides and displaying beautiful veneer flowers. Inside, the cabinet had a number of small drawers, each sightly different in size to the other, pulled open by round, nut like, wooden knobs. The cabinet held many trifles and trinkets. Similar to the clock, it was a carefully crafted object which opened up a world of private, intimate imaginings of a child.

I once spoke to a French nun who told me that when their habits were changed to those much resembling practical common clothing, there ceased to be any vocations. It made me realise how veiling creates a mystery, and mystery draws us in, it speaks to our deeper, gentler senses. Mystery is a doorway to our own inner worlds.

The containers which so enlivened my imagination as a child have been hand-crafted, “build [...] up with worn-out tools.” 19

The necessary skill and sensitivity, contained in the person of the craftsman and transferred onto the object through the making process, is beauty and knowledge made visible. Whilst handmade objects can be copied in their form or decoration, they are always unique in their imperfections and differences. This brings me to my last image, well known and forever haunting, the prehistoric hand print from Pech-Merle in Occitania [figure 7]. Like so many other such hand prints found across Europe and around the world, these most basic human markings made in ochres, probably by the means of a delicate spitting technique, between 25000 and 16000 years ago, were done inside a cave, hidden in the depths of the ‘womb’ of the earth.

It is hard to describe the profundity of this simplest of signs, left for a reason forever concealed from us within the passage of time. But without knowledge of its intention, whether artistic, arbitrary or spiritual and ritual, we can read it in a manner quite basic. As a mark left by a human who fought for his or her survival and carved his or her life here on earth with bare hands. The prehistoric craftsman has left us an image we can still relate to. It was left for us in a cave, a container where early people found shelter from the outside world, so violent, unpredictable, dangerous and mysterious, both confusing and overwhelming. A treasure which remained in the dark safety of the pyx of our planet, until our generations were so fortunate, although I wonder if worthy, to have disclosed it.

•

1 “[...] in Christianity receptacle in which the Eucharistic Host is kept.” Collins English Dictionary.

2 Marriage Chest, Wolfram Koeppe, Metropolitan Museum of Art website publications, 2006.

3 A Marriage casket and Its Moral, Georg Swarzenski, Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts Vol. 45, No. 261 (Oct., 1947), p.55, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1947.

4 A Marriage casket and Its Moral, Georg Swarzenski, Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts Vol. 45, No. 261 (Oct., 1947), p.55, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1947.

5 Lays of Marie de France tr. Eugene Mason, p.10, J.M. Dent & Sons, 1954.

6 Marriage, Dowry and Citizenship in Late Medieval and Renaissance Italy, Julius Kirchner, p.64 University of Toronto Press, 2015.

7 Because ‘no matter how much one eats of the fruit it does not satisfy one’s appetite for it’ Die Pflanze in der mittelalterlichen Tafelmalerei, Lottlisa Behling, Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, Weimar, 1957.

8 The Garden of the Renaissance, Mirella Levi D’Ancona, Firenze 1977.

9 “Play, oh guitar of mine, do not tire. The player gives you the right beat. Awaken, for one doesn’t sleep when he is in love, make a bed of violets, [...] and coverlets of sweet basil.” Sona a’ battentii, Giuseppe De Vittorio, contemporary traditional song from Puglia, Italy, tr. Ricardo Duranti, Fra Diavolo, Accordone, Italy, 2010.

10 “Play, oh guitar of mine, do not tire.” Sona a’ battenti, Giuseppe De Vittorio, contemporary song in traditional manner from Puglia, Italy, tr. Ricardo Duranti, Fra Diavolo, Accordone, Italy, 2010.

11 “This little bird which sings so sweetly [...] ‘I burn with love’. And it calls its love, who replies ‘I too burn with love’. May you be blessed, loving, tender, pretty little bird.” Quell’augellin che canta, Giovanni Battista Guarini, Il pastor fido III,3, for Claudio Monteverdi’s Fourth book of Madrigals, 1603 tr. Silvia Reseghetti and Robert Hollingworth, Polyphonic Films, 2007.

12 Gilbert White, excerpted from letters to the Hon. Daines Barrington, Letter 43.

13 A Marriage casket and Its Moral, Georg Swarzenski, Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts Vol. 45, No. 261 (Oct., 1947), p.61, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

14 Wind, Sand and Stars, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Pan Macmillan, 1975.

15 Relics and Their Veneration, Arnold Angenendt, Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe, p.19, The British Museum Press, 2011.

16 Alan Mitchell, contemporary painter, http://alanmitchellartblog.blogspot.com

17 Oxford Dictionary.

18 The Highly Sensitive Person, Elaine N.Aron, Ph.D. Thorson Classics, 1999.

19 If, Joseph Rudyard Kipling, 1895.

•

•